The Center is honored to publish with permission a statement by Rabbi Wes Gardenswartz, Senior Rabbi, Temple Emanuel, Newton MA, delivered at the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism Biennial, December 9, 2019 – 11 Kislev 5780.

Background: I was asked by the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism to participate in a panel to discuss interfaith marriage. The views in this statement are mine alone. I do not purport to speak for our synagogue, our board, or my colleagues. This is from me, not from Temple Emanuel. These are words from my heart, and I recognize and totally respect that reasonable people can reasonably disagree. We are deeply blessed to inhabit a religious tradition, and a thriving community, that can handle difference, diversity, and complexity with love and with mutual respect.

Rachel and Christopher walk into my study. Rachel grew up at Temple Emanuel, a Conservative shul in Newton, MA. She went to our religious school. Had her Bat Mitzvah here. Remained active in USY. She always assumed she would marry a Jew. She only dated Jews. She just didn’t have any mazal in finding a partner. In fact, often when she told the Jewish men she dated that Judaism was important to her, all too often what she got back in return was disdain. They would share their bad religious school story. They could not understand how any adult could take this stuff seriously.

One day, when not even looking, not on an app, not on a blind date, just in the ordinary course of life, she meets Christopher. Christopher is not Jewish, but he does not see himself as connected to any religious tradition. He is thoroughly unchurched.

Rachel and Christopher become friends, and then more than friends. They have a connection that is organic and deep. They fall in love. While Christopher is not Jewish, he deeply respects Rachel’s Jewishness, and he wants to support her. They would like to get married, and now Rachel, who has known me for 23 years, and her fiancé come to ask me to officiate at their wedding. They are both 33 years old.

It would be great if Christopher would convert. Conversion would clearly be our preferred option. We would move heaven and earth to encourage him to convert if he were open to it. But here is what he says.

He says: I love Rachel for who she is. I want to be loved for who I am. Maybe in time I might choose to convert, but I want to do it for the right reasons, and in the right time. The right reason is that this is something that I want to do, that I am drawn to. The right time is when I feel ready. I don’t want to do it to make her parents happy, or to make clergy happy, or as a condition to a wedding. I am happy if our children are raised Jewish. I would be partners with Rachel in their getting a Jewish education. But I am not ready to convert to Judaism unless I feel it is something I want to do because it feels right to me.

I think Christopher’s position is perfectly reasonable. I believe officiating at their interfaith wedding is the right thing to do at the Jewish level and at the human level. Let’s take them in turn.

Why is it the right thing to do at the Jewish level? Because whatever response we offer Rachel and Christopher is a three-generation response. Don’t miss this point. If you remember nothing else of what I said, remember this: No is a three-generation no. Yes is a three-generation yes.

If we say no, what will happen? Does anyone seriously think that Rachel and Christopher will not get married if I say no? Of course not. There is a 100 % chance of them getting married. Perhaps they will get married by a justice of the peace; or by a friend or sibling deputized as clergy for the day; secular contexts devoid of Yiddishkeit. Secular contexts which will not lead into a future of Jewish engagement, especially since their rabbi said no.

The best case, for their Jewish future, is that they will be married by the fabulous Reform rabbi, of the thriving Reform synagogue, the next town over. That is good for them. Good for their Jewish future. Good for the Reform synagogue. Bad for us. Rachel and Christopher will join that Reform synagogue. When their children are born, they will be educated at that Reform synagogue. And then it is inevitable, as the sun rises in the east and sets in the west, that at some point Rachel’s parents will send a note to our executive director saying: We are joining the Reform synagogue where our children and grandchildren are members. Feel free to release the high holiday seats we have had for the last thirty years. A no is a three-generation no. A three-generation no will hollow out our communities. It is already happening. We know this.

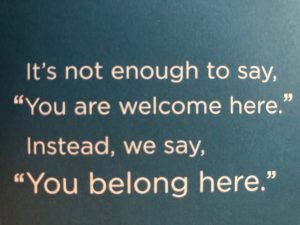

Walk into most Conservative shuls on a Shabbat morning. You see a lack of young people. We don’t have engaged young adults. We need Rachel and Christopher. We need Rachel and Christopher’s children. We need Rachel’s parents. If we want Rachel and Christopher, their children, their energy, no is not the way to go. It makes no sense to say you are welcome into our shuls, after you are married by somebody else, when the very fact that our clergy will not marry them makes them feel not welcomed.

What happens if we say yes? Yes is not a guarantee. But yes is better, and here is why. If I officiate at Rachel and Christopher’s wedding, then I will meet with them six times, six one-hour sessions, before the wedding. That creates connection. That creates relationship. If they live in Boston, they will join our shul. When they have children, they will attend our schools. If I say no to their wedding, what they hear, and what they feel, is no. I don’t get the six hours with them. Panting after them after the wedding which I spurned to say, hey, I can put up a mezuzah for you, is not going to work.

But saying no to Rachel and Christopher is also the wrong human move. For me, this is the beating heart of this whole matter.

Our biggest problem is not intermarriage. Our biggest problem is the loneliness epidemic in America. Too many of our children are lonely. Too many of our children come home to an empty apartment. Too many of our children have nobody to share their day with. Too many of our children have nobody to share their life with. Too many of our children have looked but have not found. Too many of our children have been dancing at other people’s weddings but not at their own. Too many of our children have wondered and worried will my day ever come? Rachel’s day came. She found her mensch. She found her match. She is genuinely happy. I am genuinely happy for her. No asterisks. No qualifications. Happy that at long last she has a companion to walk with in life. I want to be there to celebrate with her.

Now I know that many here disagree with me, passionately. And that is fine. The last thing I am trying to do is impose my views on anybody. I just don’t want to have anybody’s views imposed on me. I don’t want New York deciding these intimate and crucial issues for me.

Let rabbis in the field decide. The very fact that we are having this conversation suggests multiple points of view and abundant good faith and goodwill. Some rabbis might be comfortable doing the entire ceremony. Others may prefer to stand with the couple under their chuppah and offer them blessings and words of love but not officiate. Others might hew to the traditional position. Let each rabbi figure it out on his, her or their own.

Bet on us. Bet on our moral and religious intuitions. Bet on our love of the Jewish people and humanity. Bet on our ability to do the right thing as we see it. Thank you.