Remarks at 2019 URJ Biennial Learning Session, Embracing Interfaith Inclusion in Your Congregation

Inclusion is more than welcoming. That’s what advocates for other marginalized Jewish groups, including LGBTQ people, people of color, and people with disabilities, all say. One consultant explains that welcoming leaves a visitor feeling that his or her presence as a guest was truly appreciated. “[I]nclusion is a much deeper form of acceptance… [O]nly genuine inclusion will convince me to remain part of the community. I will stay if I feel I truly belong.”

I was at the United Synagogue biennial earlier this week. They showed a beautiful video created by the United Synagogue and the Ruderman Family Foundation, a leader in disability inclusion. After steps were taken to help an elderly man who had difficulty hearing, he said, “we’re not guests here, we’re part of it.” That’s the difference between welcoming and inclusion.

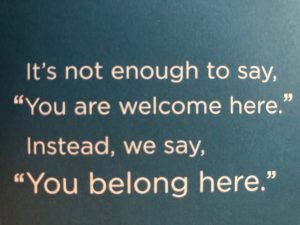

On the screen is part of a flyer from the Rashi School, a Reform day school in the Boston area, which says: “It’s not enough to say ‘you are welcome here.’ Instead, we say, ‘you belong here.’” That’s the difference.

Our movement’s resolutions concerning other marginalized groups all set a goal of inclusion: they speak of goals “[T]o integrate fully all Jews into the life of the community regardless of sexual orientation;” “[W]elcoming communities of meaningful inclusion, enabling and encouraging people with disabilities … to participate fully …;” or of “[C]ommitment to the full equality, inclusion and acceptance of people of all gender identities and gender expressions.”

But the movement’s latest resolution on interfaith marriage commits only says partners from different faith backgrounds “deserve a warm welcome” and appreciation, while also encouraging conversion, “becoming a fully Jewish family.”

Like every other marginalized group, it stands to reason that interfaith couples will not stay unless they are made to feel that they truly belong. That’s what inclusion means.

If we require people to convert in order to feel that they belong, they won’t and we will dwindle. I’m wearing a sticker with a large “72%” – that’s the rate of interfaith marriage among non-Orthodox Jews, and it means that 84% of new households being formed that include at least one non-Orthodox Jew are interfaith households.

How do we enable people who are not Jews to feel that they truly belong in Jewish communities? We need three things: a new understanding of interfaith marriage, and adapted attitudes and policies that support full inclusion.

First, in the traditional view, Judaism is for Jews; what matters is “being” Jewish, part of the Jewish people. Those who identify as Jews are “in;” a partner who is not a Jew is “out” or “other.” We need a new understanding that Judaism is not just for Jews, it is for people who are “doing” Jewish, whether or not they identify as Jews, in a community that consists of other Jewishly-engaged people. This is radical, because it stands the traditional view on its head.

A rabbi told me once that it didn’t make sense for someone to say, “I live Jewishly but I’m not a Jew.” We need a new understanding of interfaith marriage in which that makes perfect sense.

Second, inclusion requires an adaptation of underlying attitudes towards the group to be included. That means considering interfaith families as equal to inmarried families, and partners from different faith backgrounds as equal to Jews. Unfortunately, examples of expressions of negative attitudes abound. Expressing a preference that our children marry Jews delivers a message of disapproval to the 72% of them who will intermarry anyway. The Hebrew Union College policy to not admit or ordain intermarried rabbinic students sends a message of disapproval. Feeling disapproved of is not conducive to feeling belonging.

Third, inclusion requires adaptive change in the established system with which the group to be included engages. As a consultant explains: “Modes of worship may need to broaden. Methods of decision-making may need to change. And interaction patterns among members may need to evolve.”

Adaptive change means not just considering, but treating interfaith families and partners from different faith backgrounds as equal. What leadership roles can partners from different faith backgrounds take? In what rituals can they participate? How will we explain those policies and communicate our invitations to engage?

I received a very negative email from a rabbi a few days ago. He said that boundaries are essential to the survival of our culture; that if partners from different faith traditions can do everything Jews can do, Jewish identity would be meaningless and why would anyone convert; that it’s like citizenship, where aliens have certain rights but can’t vote; and that churches don’t allow everyone to take communion.

Here’s how I responded. Yes, we can maintain boundaries, and apply the citizenship analogy – and we won’t have anyone left to engage in our beautiful culture that we want to survive – remember the 72%/84%. Hopefully people convert because it is existentially important to them to identify with the way that they live, not so that they can exercise certain rights that others can’t. I’m not an expert on communion, but my understanding is that it can only mean affirming the divinity of Jesus; that’s qualitatively different from partners from different faith traditions feeling that they belong, that they are part of the “us” to whom God gave the Torah, and can authentically say a prayer thanking God for doing so.

[…] I said at the learning session, addressing what inclusion means, maintaining high boundaries and applying the citizenship analogy – essentially, requiring […]