Seven years ago, the Pew Report found that 72% of non-Orthodox Jews were intermarrying. One of its many other findings – that while 89% of intermarried Jews were proud to be Jewish, only 59% had a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people (51-2) – raises the question whether interfaith couples feel welcomed and included in Jewish communities.

Since the Pew Report, the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies at Brandeis University has conducted four studies of interfaith couples and eleven local Jewish community studies, analyzed by the Center for Radically Inclusive Judaism in a recent paper. What surfaces repeatedly in both bodies of research is the feeling of being “other” that people in interfaith relationships say they experience. We believe that the impact and extent of that feeling of being “other” explains the Pew Report’s finding that interfaith families do not feel that they belong to the Jewish people, and points the way to what needs to be done to engage them.

Studies of Interfaith Families

The 2019 Beyond Welcoming: Engaging Intermarried Couples in Jewish Life study stated “we have succeeded in making intermarried families feel welcome,” and that “barriers to engagement with Jewish life have been largely eliminated.” These statements were premature declarations of victory, in part because of the study’s own statement that interfaith couples who did not feel completely welcome “emphasized their feelings of being ‘other’ and not fitting in.” (42)

The Swimming Upstream: Interfaith Families in Toronto study, released in August 2020 and largely unnoticed in the midst of the COVID pandemic, is inconsistent with the declaration of success at welcoming. It states that “Couples felt unwelcome when interfaith relationships were denigrated, when the non-Jewish partner felt pressure to convert, or when they were expected to negate or hide the non-Jewish partner’s religious identity.” (1) It repeatedly describes interfaith couples’ feelings with words like “outcasts,” “outsider,” “inferior option” and “undesirable” (emphasis added):

[T]o be accepted as part of a community with families like ours would be nice for us. We feel like outcasts sometimes. (Non-Jewish partner, survey) (14)

One partner often feels like an outsider, so it’s difficult to prioritize events/feel comfortable attending. (Jewish partner, survey) (33)

“[T]he desire to be seen in a positive light and not denigrated as an inferior option, inherently less Jewish, or dysfunctional” was what they most wished the Jewish community understood about them. (28)

Couples fear some Jewish institutions will view them and their families as undesirable or unfortunate. (41)

While the tone of the two other studies of interfaith couples, in Boston and Pittsburgh, are generally more positive about the interfaith couples’ experiences, still in Boston, in some cases, “despite the initial welcome by a congregation, couples felt an undercurrent of disapproval or being treated as outsiders rather than as integral and valued members of the community” (17) and in Pittsburgh, some non-Jewish partners worried that their acceptance might be conditional or superficial and were concerned that they or their children were thought of differently or more negatively than inmarried couples and their children (12)

The Toronto study finds that “Many interfaith couples indicated they felt pressure from family, friends, and religious leaders for the non-Jewish partner to convert to Judaism.” In Toronto and in Pittsburgh (12), expectations about conversion felt unwelcoming, judgmental and intrusive.

I wish that the Jewish community didn’t put so much emphasis on having a Jewish spouse or partner. I find it highly offensive when my husband’s siblings speak about not accepting if their children were to date someone who wasn’t Jewish. It is offensive to myself and my daughter and really turns me off of the religion. (Non-Jewish partner,Toronto survey) (28)

Families are perceived to be more welcoming than community organizations. In Toronto, “Non-Jewish partners especially appreciated welcoming messages and actions that made them feel they belonged in their new extended families.”

When I first met [Jewish partner’s] parents, it felt like I was kind of already part of the family. I wasn’t the outcast. They’re very welcoming and very friendly. (Non-Jewish partner, interview) (30)

Feeling welcomed in families but not in Jewish organizations may explain why 89% of Toronto surveyed couples engaged in some celebration of the High Holidays, but 76% did not attend services, celebrating instead in home settings with family or friends. (13)

Local Community Studies

A. Interfaith Families Connection to Jewish Community

In the Twin Cities, as one example, 48% of intermarrieds feel not connected to either online or local community, compared to 8% of inmarrieds. (52) The following average data from the local community studies suggest that interfaith families do not experience being welcomed or made to feel part of Jewish communities:

- Fewer intermarried (25%) than inmarried (54%) respondents said that being Jewish is very much a matter of community. Fewer intermarried (57%) than inmarried (89%) respondents said that being part of a Jewish community is important or essential to what being Jewish means to them.

- Fewer intermarried (5%) than inmarried (28%) people say that they feel very much of a connection with or very much like a part of their local Jewish community.

- Fewer intermarrieds (18%) than inmarrieds (43%) said they feel very much connected to Israel, a traditional measure of feeling part of the Jewish people.

B. Welcoming

People in interfaith relationships generally found their local Jewish organizations and community less welcoming than inmarrieds did. Six of the studies explicitly asked how welcoming the local Jewish community was to interfaith families; 54% of intermarrieds, compared to 69% of inmarrieds, said their local Jewish community was a little/somewhat or very much welcoming; more intermarrieds (42%) than inmarrieds (25%) said they had no opinion.

In Boston, for one example, 20% of intermarrieds compared to 8% of inmarrieds said that not welcoming was a reason they did not give their children Jewish education (TA 42). In Baltimore, as another example, only 15% of intermarrieds very much agreed that local Jewish organizations were welcoming to “people like you,” compared to 46% of inmarrieds. (TA (Technical Appendices) 121) The executive summary of the Baltimore study bluntly states: “Households that include an intermarried couple tend to feel that the community is not welcoming to them, does not care about them, and does not support them.” (3)

C. What Interfaith Families Say About Welcoming and Inclusion

Several local community studies invited comments about what prevented people in interfaith relationships from participating in Jewish life. In Baltimore (82) some interfaith families “felt unwelcomed in Jewish spaces, or feared they would be, because of who they are – in some cases, this belief was a result of direct experience and in others, it was an assumption.”

My wife is not Jewish, so my children are not Jewish according to Halacha, even though I am teaching them about Jewish culture. I feel like my family and I may not be accepted by the Jewish community.

As the non-Jewish spouse in a Jewish family, I am worried I won’t be accepted and have felt that way in some Jewish events in the course of my relationship with my husband. (84)

In the Twin Cities, despite a general feeling that the community is supportive of their needs, “some members of interfaith families, expressed their struggles with feeling accepted and welcomed.”

A major gap is making interfaith families feel welcome, especially the non-Jewish partner. This keeps us from being more involved when one person doesn’t feel welcome. (120)

In Pittsburgh, interfaith families felt that the community could do more to make them feel welcome.

We have a mix of religions in our home, though in practice we only practice Judaism. We found that we were not always welcomed or respected at [our area] congregations. Even Reform ones. (90)

In Washington, some interfaith families reported ways that the community made them feel unwelcome. One said,

As someone from an interfaith household, it’s hard to engage with the community if I have to convince my spouse, ‘Don’t worry, you’ll feel comfortable and welcome.’ She often feels like the Jewish community is insular and skeptical of non-Jews, and that makes it hard for me to find ways to engage in the community as well. (93)

Dual Faith Families

Data from the local community studies show that 15% of the children of intermarried parents are being raised Jewish and another religion. In the Twin Cities local community study (24) and the Boston study of interfaith families (17-8), some couples expressed concern about not being fully accepted if they decided to raise their child in two religions, or include both religions in their home life and in their identification of themselves as a family. One Boston respondent said:

There are some resources that say that they’re open to interfaith couples… But, it’s framed as for folks wanting to build a Jewish home … What I hear about interfaith [is]couples where one person is Jewish, and a Jewish community accepts that because they’re going to raise their kids Jewish. We are going to raise our kids Jewish, but we’re also gonna raise them actively something else… I feel anxious about finding those resources that don’t want me to be a kind of blank… I’m not a ‘nothing’ religiously. (Non-Jewish partner) (17-8)

What Can Be Done

The local community studies typically end with recommendations for future action. The Pittsburgh study clearly states the two main lines of efforts needed to engage interfaith families:

If the community can increase its outreach to intermarried families to make them feel more a part of the community, and if the community can offer them programs that stimulate their interests and meet their needs, there may be a significant opportunity to increase their Jewish engagement and encourage their children to develop their Jewish identities. (90)

There is a great deal of data and comment in the Cohen Center’s research that supports the view that people in interfaith relationships feel less welcomed and less a “part of” than inmarried people do. What a significant segment of people in interfaith relationships say, demonstrates a persistent feeling of being “other.”

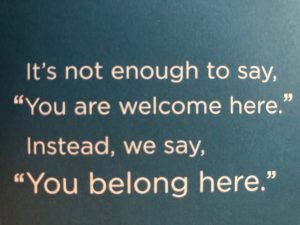

Some of their comments point the way forward. One from the Boston study of interfaith families highlights the difference between feeling welcomed as a guest and included as part of the community: “Some couples recounted being regularly welcomed when they attended activities at a synagogue but never really progressing to feel like they belonged in the community.” (17)

Inclusion requires treating partners from different faith backgrounds as equals, like the Jewish partner’s Toronto family who treat the partner from a different faith background “as if I’m Jewish” (31), or the congregation in Boston where both partners are “treated very equally as members of the community” and are “both equally members of the congregation and that is really, really important to the fact that we feel at home here.” (16)